Wes Streeting has just launched Labour’s 10-year NHS health prevention plan with a key pillar to move from treating sickness to preventing disease. This is a great objective, but what does it actually mean?

For older people, extending the healthy face of life and compressing the period of disability would be transformative. ONS data shows that today in the UK men and women spend the last 17 and 22 years respectively with a disability that limits their day-to-day activities. This gap was even larger for the lower socio-economic groups.

This gap is largely as a result of decades of excess living, bad habits or substance addictions (e.g. tobacco or alcohol). By the time a medical issue has been detected, often due to an acute episode, much of the health damage has been done. In addition, some conditions, such as obesity, are worsened by financial struggles, leading to poor food choices, living conditions and working hours.

Balancing Freedom of Choice and Good Health

In the UK there is a strong presumption of freedom of choice, even when these can cause self-harm. Large businesses often exploit this with products that are addictive or harmful. The government must strike a balance between, personal liberty and public health. Invariably this means only intervening when the product would cause material harm to ourselves or others. Smoking is the most obvious example.

Ideally, people should make informed choices about their lives, which would suggest that disclosure is the best approach to balancing freedom of choice and good health. However, most often decisions are based on convenience, cost of habit.

Libertarian paternalists, who look to influence behaviour while still respecting the freedom of choice, would propose using behavioural design techniques to encourage people to make better choices without banning bad ones. Ideally, health prevention strategies should be personalised and focus on small achievable goals.

Governments could use two main approaches to prevention: the carrot (subsidies and incentives) or the stick (legislation and taxes).

The Stick Approach: Legislation and Taxation

Legislation: Legislation could ban or control access to harmful products. For example, the UK outlawed Class A drugs, mandated wearing of seatbelts and banned smoking in public places. A more recent proposal by the Conservatives, inspired by New Zealand, is to ban cigarette sales to anyone born after a certain date, to create a smoke-free generation.

A ban could be extended to certain ultra-processed foods, which have known health issues. Whilst no other country has gone so far, many have adopted strict labelling laws. This could be strengthened with standard warning signs, such as those on cigarette packets. However, none may be ineffective, especially when the foods are cheap.

The alternative to banning foods by category would be to ban specific harmful food ingredients and additives. For example, in the UK we ban chlorine-washed chicken, which is used in the US to reduce bacterial contamination on low-cost factory reared chickens.

Taxation: Another approach would be a progressive health tax. The UK’s soft drinks with added sugar has been successful in pushing manufacturers to reformulate their products to reduce the sugar content. Another recent example is beers taxed on their alcohol strength, which made Grolsch reduce their alcohol content in the UK.

This could be extended to highly processed products, or foods high in salt, or saturated fat products. VAT could be an effective lever. Today there is zero VAT on basic foods, but standard VAT applies to foods considered to be luxury or highly processed. Other countries have adopted a so called “junk-food tax” with positive outcomes, as manufacturers have reformulated their products and consumers have switched to healthier alternatives. However, the biggest challenge remains balancing long-term health outcomes with affordability, especially for low-income families.

The Carrot Approach: Subsidies, a Health Lottery and Personalised Prevention

Subsidies: The opposite of a tax is a subsidy. The UK has used subsidies to promote the use of environmentally products such as solar panels, heat pumps and Electric Vehicles. In health, the government heavily subsidises prescriptions, with many groups receiving them for free. Statins, used to lower cholesterol, are a great example of a low-cost preventative health strategy. Vaccines to lower or eliminate population disease are another.

Healthy eating subsidies already exist in the UK through the Healthy Start scheme, which provides vouchers to pregnant women and families with young children, for milk, fruits and vegetables. The vouchers could be extended to low-income families purchasing fresh fruit and vegetables, or to promote physical activity by subsidising gym membership or entry to the swimming pool.

To be cost effective the subsidies need to be targeted and sustainable over the long-term. A concern about untargeted subsidies is their long-term public cost, with free milk program for school children being eventually scrapped due to costs.

A Health Lottery: A more radical approach would be to link prevention to a health lottery. In addition to the normal purchase of lottery tickets, people would be given free entries by completing healthy activities. For example, buying healthy foods, or completing gym sessions or park runs would earn points that could be converted into lottery entries using a bar code receipt scanned by the lottery organiser. The free tickets and winners could be promoted on social media to create a viral effect at a much lower cost than an open-ended food subsidy.

The benefit of a health lottery is that it focuses on nutrition and exercise, both of which are critical in health prevention. The scheme could also be widened to include mindfulness and even medication management.

Personalised Prevention: Our medical records should provide smart data on our health, including family history, weight, tobacco use and medication. These will be digitalised as part of the NHS IT upgrade and could be used to design a personalised prevention plan.

With advances in AI, our medical records could be scanned to identify early trends in say weight, blood pressure, insulin resistance, etc. The AI could then deliver targeted health advice and information or recommend further medical tests or consultations. The AI advice could extend to other health prevention measures such as attending health clubs, mindfulness classes or community events. These could be made available at low cost or free with a subsidised voucher scheme.

A personalised intervention plan would be a more cost-effective approach to health prevention compared to the use of broader subsidies.

Of course, the success measure would depend on whether a personalised intervention plan delivers lasting behaviour change.

Changing the Concept of Age: Biological Age

To drive home the importance of prevention, we should shift from measuring age chronologically (by birth date) to biologically (by how our bodies are ageing). Including biological age in our health records should prompt health advisers to inform their patients of how they can manage their long-term health. The difference between chronological and biological age could be a powerful motivator for many individuals to adopt healthier habits.

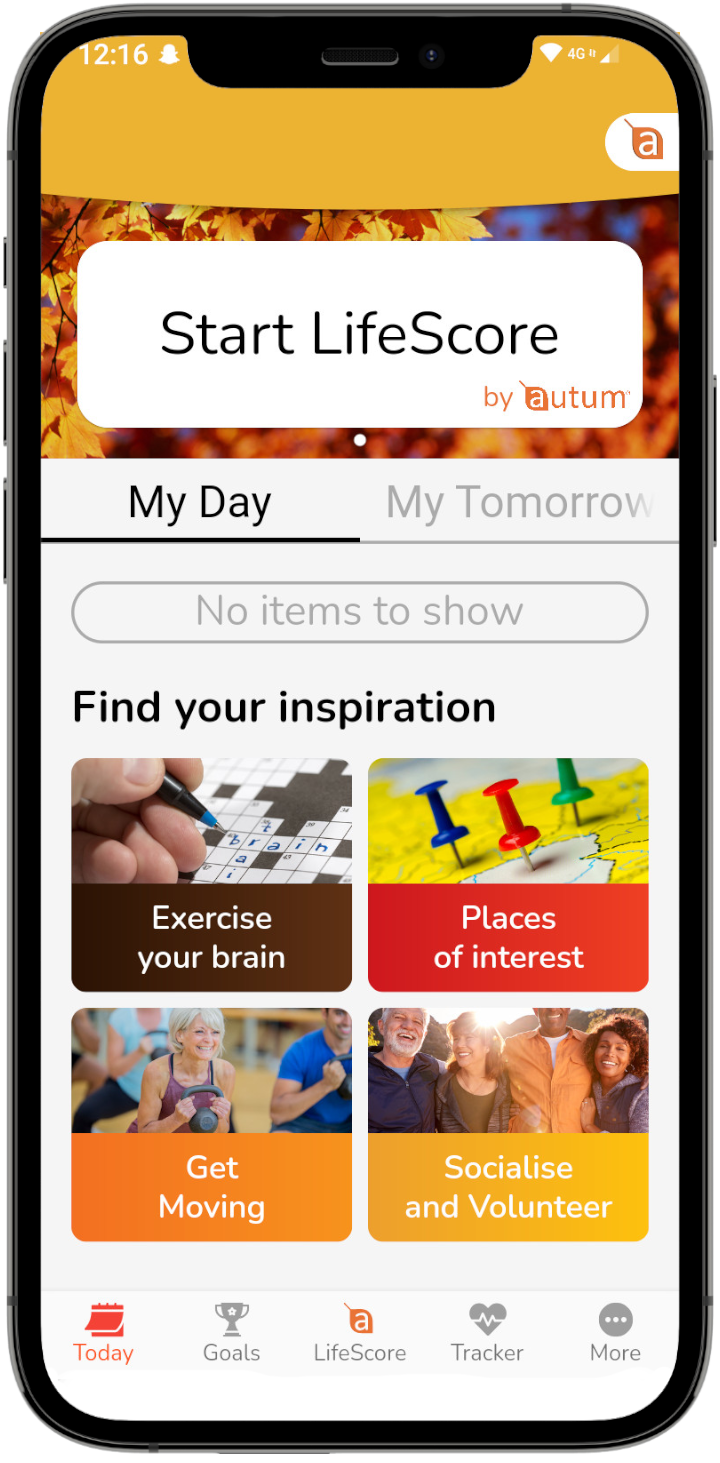

At Autum, we believe that empowering people to take small steps to lower their biological age is crucial to health prevention. Download the Autum app (Android or IoS) to try our biological age calculator and find inspiring activities and content to help you begin your journey.

A passionate entrepreneur who has spent years calculating life risks and has set up two successful innovative businesses. He believes with the right motivation and support we can extend healthy life. This is now his calling and has found a great team to make it happen.